Environmental Law: The Supreme Court’s Hawkes Co. Decision May Help Save Your Project When Wetlands are Present - June 2016

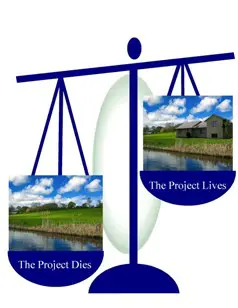

Wetlands make it hard to build at a property. This is especially significant in Hampton Roads, Virginia, due to the high prevalence of wetlands in this part of the country. The builder and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Army Corps) do not always agree on the size of the wetlands footprint, with the builder needing the footprint to be small in order for the project to go forward, and the Army Corps claiming the footprint is large, which can kill a project. Until yesterday, in most parts of the nation (including Hampton Roads), the builder could not get a Court to review the two competing views on the size of the wetlands footprint until the entire Clean Water Act permit process had run its course and was complete. This was a strange result because the differing viewpoints as to the size of the wetland footprint are finalized early in the permit process, when the Army Corps issues its “approved Jurisdictional Determination”, or “approved JD”. Forcing the builder to wait for the rest of the permit process to play out (before going to Court) takes a couple of years and costs $200k+/-. The builders who could not afford either the uncertainty or the cost typically abandoned the project or capitulated to the Army Corps. That all changed yesterday when the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case U.S. Army Corps of Engineers v. Hawkes Co., 578 U.S. ___ (2016), ruled that the builder can get immediate Court review once the Army Corps issues the approved JD, and the applicant has availed himself of the administrative appeal afforded at 33 C.F.R. §331.4.

What are Wetlands and why do they Matter?

A narrative describing the role played by President Richard Nixon, and other events, leading up to the adoption of the Clean Water Act in 1972 (CWA) is beyond the scope of this article but available elsewhere. What is relevant to our purposes here is that the CWA at 33 U.S.C. §1311(a), and in the definitions at 33 U.S.C. §1362, require a person to get a permit before “any pollutant” may be discharged (from a point source) into “the waters of the United States”.

The word “wetlands” appears nowhere in the CWA. A water body, however, typically has a transitional strip of soggy land lying in the zone between the water body and the dry land above it. Depending on topography, this soggy strip of transitional land can be narrow or quite wide. The “waters of the United States” end only when the upland is reached, hence the soggy strip of transitional land forms a part of “the waters of the United States” and has been given the shorthand label “wetlands”. There are approximately one million acres of wetlands in Virginia; 25% are tidal wetlands, and the remaining 75% are non-tidal. Nearly all of these 250,000 acres of tidal wetlands are found in and around coastal Virginia, in addition to the non-tidal wetlands also found here.

Land on the water is much sought after. People routinely pay a premium to own (and build on) land on the water. One common strategy that can dramatically increase the buildable footprint is to place dirt and other “fill” material into the wetland area thereby converting it from wetland to upland. Doing so, however, is illegal unless a permit is obtained, as provided at 33 U.S.C. §1344(a) and as further defined in the implementing regulations promulgated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Army Corps). Testament to the financial upside of filling wetlands, people spend over $1.7B each year to obtain wetlands permits. Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715, 721 (2006). Filling wetlands without a permit can greatly increase the value of property but only at the risk of criminal prosecution or civil enforcement. For example, when Mr. Rapanos, with no permit, backfilled wetlands on a parcel of land in Michigan that he owned and sought to develop, twelve years of criminal and civil litigation ensued. Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715, 721 (2006). The U.S. Supreme Court in its Hawkes Co. decision once again echoed the Court’s continuing recognition of the “serious criminal and civil penalties” that attach to the violation of the Clean Water Act.

New Interpretation by the Army Corps Expands Wetlands Footprint and Reduces the Buildable Footprint

Owners, developers and builders in coastal Virginia are feeling pain from a change in the way that the Army Corps is interpreting the wetlands rules, with the Army Corps in many cases telling people that they have far less buildable land than was expected. The justification for the Army Corps’ new approach is a document that the Army Corps issued in late 2010, nearly six years ago, but few in the development community noticed at the time because construction activity in coastal Virginia ground to a halt during the recession of 2007 to 2009, and is only now picking up again. Expanding the size of the wetlands area at a property often time is the death knell for a construction project because it reduces the buildable footprint.

Delineating Wetlands at the Property

Through a process known as “wetlands delineation” a consultant retained by the owner, developer or builder determines if wetlands are present on a site and, if so, establishes their boundaries. The consultant should have strong subject matter and local expertise, such as that possessed by Kerr Environmental Services in the Hampton Roads market. The wetlands delineation is submitted to the Army Corps after which the Army Corps makes a “confirmation site visit”. The difficulty arises when the Army Corps insists that there are wetlands at areas that the consultant determined were non-wetland, oftentimes with many hundreds of thousands of dollars, or the survival of the project itself, hanging in the balance.

The federal regulations at 33 C.F.R. §328.3(b) define “wetlands” but do not explain how to determine whether wetlands are present at a property nor how to establish the boundary between the area of wetlands and non-wetlands. The procedure for conducting a wetlands delineation is found in the “Corps of Engineers Wetlands Delineation Manual”, issued in 1987 (1987 Delineation Manual). Over time the Army Corps came to believe that regional differences called for adjustments to the national delineation manual. The Army Corps in 2002 published its rationale for adopting regional modifications. The adjustments applicable to coastal Virginia came out in November 2010 by way of the “Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain Region” (Regional Supplement).

Before an area can qualify as a wetland, the 1987 Delineation Manual requires the presence of three characteristics: (i) hydrophytic vegetation; (ii) hydric soil; and, (iii) wetland hydrology. If one or more characteristic is absent then the area is non-wetland. However, relying on chapter 5 of the Regional Supplement, the Army Corps is now designating areas as wetland even though “no indicators of hydrophytic vegetation are evident.” (Regional Supplement page 117). Similarly, the Army Corps relies on Chapter 5 of the Regional Supplement to designate areas as wetland even though “hydrology indicators appear to be absent” (Regional Supplement page 135). The result is an expansion in the wetlands footprint which can turn a promising project into a big money loser that must abandoned.

Immediate Court Review of the Approved JD

With such large dollars riding on the results of the wetlands delineation, what can be done? The regulations at 33 C.F.R. §331.4 provide for an “administrative appeal” but it will be decided by an official at the Army Corps which, it bears noting, is the agency that generated the wetlands delineation that is in dispute. The possibility of immediate court review would certainly furnish a lifeline for the owner, developer or builder looking to save the project from the Army Corps’ kiss of death. The possibility of immediate court review is, however, uncertain because creation of the wetlands delineation is but a way-station in the permit issuance process, a process which can in some cases last several years. For perspective, the “average applicant for an individual permit spends 788 days and $271,596 in completing the process, and the average applicant for a nationwide permit spends 313 days and $28,915 – not counting costs of mitigation or design changes.” Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715, 721 (2006). As the U.S. Supreme Court wrote in Hawkes Co., the Clean Water Act “permitting process can be arduous, expensive, and long.”

Many courts heretofore insisted that the applicant see the application process through to the end before coming into court. See, e.g., Fairbanks North Star Borough v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 543 F.3d 586 (9th Cir. 2008); Belle Co. v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 761 F.3d 383 (5th Cir. 2014). In other words, even though the dispute as to the wetlands delineation is fully formed early in the permit process, the property owner cannot get the Court to review it until after the property owner has waited 788 days and spent $271,596 (in the case of an individual permit). Many owners simply cannot afford the delay nor the cost in order to get their ticket into Court and so they abandon the project or scale it way back. Other courts however grant immediate review, which is quite useful to owners, developers and builders. See, e.g., Hawkes Co. v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 782 F.3d 994 (8th Cir. 2015).

In December 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal filed by the Army Corps in the Hawkes Co. case and on March 30, 2016 the case was argued in that Court. The Court announced its decision in the Hawkes Co. case on May 31, 2016, holding that owners, developers and builders may have immediate court review of the Approved JD issued by the Army Corps, provided that the applicant has exhausted administrative remedies at the Army Corps by availing himself of the administrative appeal afforded at 33 C.F.R. §331.4.

If you have questions regarding water and environmental law, contact our waterfront law team.